Multiple Inheritance

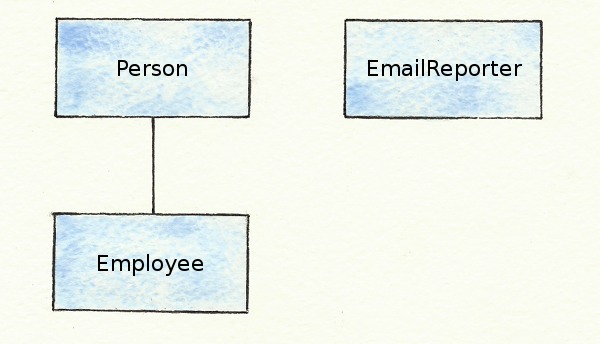

Mixins are Ruby’s way of dealing with the multiple inheritance problem. If inheritance expresses an is-a relationship, the problem occurs when a class is more than one thing. For example, it’s easy to express that an Employee is a Person by making the Employee class inherit from the Person class. But what if Employees are also EmailReporters, who can email their status to their manager? How do you express that?

class EmailReporter

def send_report

# Send an email

end

end

class Person

end

class Employee < Person

# How can this also be an EmailReporter?

end

Other languages solve this problem by allowing a single class to inherit from multiple other classes, or by using interfaces. Ruby is a single-inheritance language, but solves this problem with mixins.

Mixins

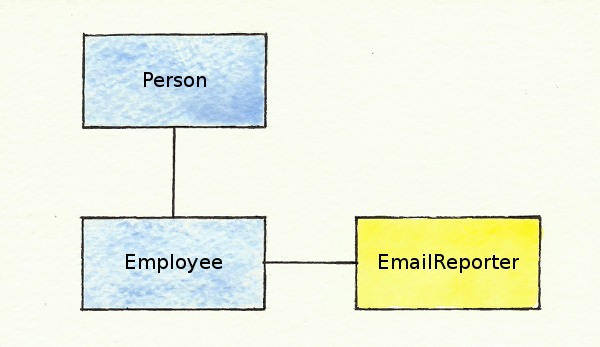

Mixins are a way of adding a set of methods and constants to a class, without using class inheritance. The include method lets you include a module’s contents in a class definition. In addition to inheriting from one other class, classes can include any number of mixins. In our example, the Employee class can inherit from the Person class, but include the EmailReporter module as a mixin. Then, any methods and constants that are defined in the EmailReporter module are added to the Employee class.

module EmailReporter

def send_report

# Send an email

end

end

class Person

end

class Employee < Person

include EmailReporter

end

Mixins have simplicity as their primary strength. They let us share code between classes without some of the problems of multiple inheritance, which can be complex and sometimes ambiguous. They let us easily create lightweight bundles of methods that can be included in any class where they’re needed. This functionality is simple and convenient, but not without its problems.

Pitfall #1

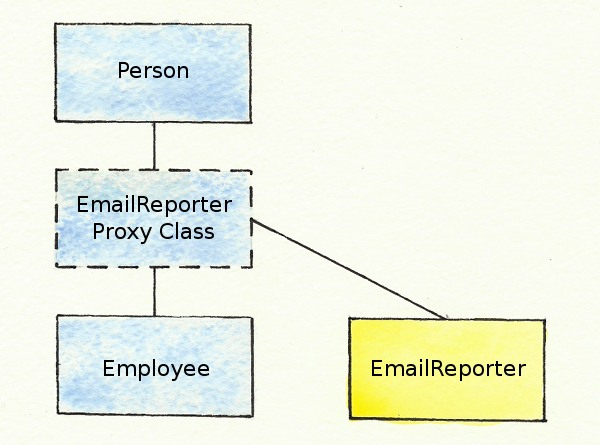

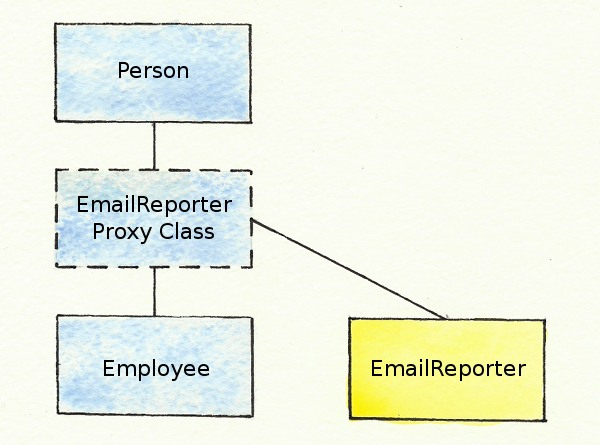

Mixins have at least two major pitfalls. The first pitfall stems from how mixins are implemented. What really happens when you call the include method with a module? It seems like the module’s methods are injected into the current class, but that’s not actually how it works. Instead, the module is inserted into the inheritance chain, directly above the class where it’s included. Then, when one of the methods in the mixin is called, the interpreter starts going up the inheritance chain looking for the method, and when it gets to the mixin module, the method is found and called.

You can see in the above diagram that the EmailReporter module is represented right above the Employee class in the hierarchy, by the class with a dotted line around it. But where does this new class come from? The Ruby interpreter creates an anonymous class called an include class (or proxy class) that is a wrapper for the module, and this class is inserted into the class hierarchy, directly above the class where it’s included.

This all works great, except when a module defines a method that already exists in some other module or class in the hierarchy. When that happens, whichever definition is lowest in the hierarchy silently shadows, or covers up, all the other methods. That means the behavior of a method call can be determined not just by the class hierarchy and which modules are included, but the order of the include statements.

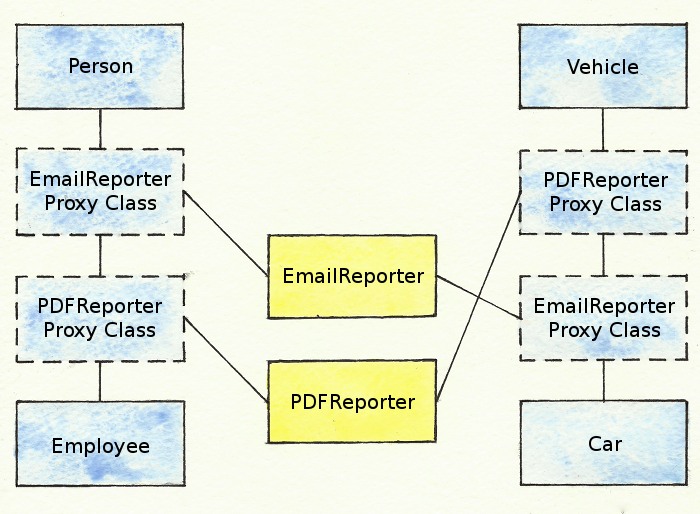

Let’s expand our previous class hierarchy to show an example of this:

module EmailReporter

def send_report

# Send an email

end

end

module PDFReporter

def send_report

# Write a PDF file

end

end

class Person

end

class Employee < Person

include EmailReporter

include PDFReporter

end

class Vehicle

end

class Car < Vehicle

include PDFReporter

include EmailReporter

end

In this hierarchy, we have added Vehicle and Car classes to our previous hierarchy. Also, in addition to the EmailReporter module which emails reports, we have a PDFReporter module which writes reports to PDF files.

Because the Employee and Car class include the EmailReporter and PDFReporter modules in a different order, calls to the send_report method have different effects:

an_employee = Employee.new

a_car = Car.new

an_employee.send_report # Writes a PDF

a_car.send_report # Sends an email

This dependence on statement ordering can be confusing and can make debugging more difficult. And this issue isn’t restricted to just modules interacting with each other. Methods defined in a class definition will silently shadow methods in included modules, and methods defined on classes higher up in the hierarchy will be silently shadowed by any modules lower down in the hierarchy.

Pitfall #2

The second pitfall of mixins is that they break encapsulation, so they can make code more entangled and make code changes harder. Consider the case of the standard Ruby Comparable module. When this module is included in a class, it expects the class to define a <=> method, which the module uses to define the <, <=, ==, >=, and > operators, as well as the between? method.

The Comparable module is very convenient, but consider what would happen if it changed so that it expected a compare_to method instead of <=>. This change would necessitate changing every class that includes Comparable. This is unlikely to happen with a standard Ruby module like Comparable, but it is fairly likely to happen with the modules you create in your application, especially at the beginning of development when you’re still figuring out how the different classes and modules should interact.

Instead of using mixins, it’s often better to create a new class and call methods on an instance of that class. Then, if the internals of the new class change, you can usually make sure the changes are wrapped in whatever method was originally being used, so the calling code doesn’t have to change.

Conclusion

In general, mixins are a good solution to the multiple inheritance problem. They can be very useful and make code sharing between classes easier than other solutions like interfaces or true multiple inheritance. However, when using mixins, you have to be aware of the potential pitfalls. Since mixins silently shadow methods, you have to be careful with method names and the order of include calls. Also, since mixins break encapsulation and can make changes difficult, you may want to consider using an instance of a class to perform the same function, especially early on in new projects.